the true story about the watch factories of death

The fight of their lives

After two years of searching desperately for a lawyer to take her case, Grace Fryer found a kindred spirit in Raymond Berry. She was soon joined by four other women: Katherine Schaub, Albine Larice, Edna Hussman, and Quinta McDonald--all of whom had worked in radium factories or had family who did.

Their demand? $250,000.

This was a daunting task. First, they struggled to find doctors who would put pen to paper and diagnose them with radioactive poisoning (a key ingredient to their suit). Berry secured the help of physicist Elizabeth Hughes, who used electroscopy to detected radioactivity. After conducting some tests, she testified that the five women were so toxic, even their breath was radioactive.

The USCR did everything it could to deny any liability for the girls' condition. They even falsified reports and threatened those who attempted to publish evidence of negligence.

It wasn't until one of the company's senior chemists (who, ironically, was instructed to wear protective gear when brewing the deadly concoction) died after suffering from similar symptoms that some were willing to concede a possible connection. It emboldened more and more doctors to testify on their behalf, confirming or at least positing, that harmful work practices and exposure to radium were the cause of the women's pain. Still, the company kicked and screamed and the lawsuit dragged on.

The women's strength faded every day as the radium worked its way through their bodies, earning them the title "The Living Dead" and giving their nickname "ghost girls" a whole new meaning.

Eventually, after a year and a half of expert debate, deliberation, and denial, the USCR approached Berry with an offer: an out-of-court settlement of $10,000 each (minus medical bills and litigation, of course). They negotiated and accepted the offer on May 30, 1928.

---

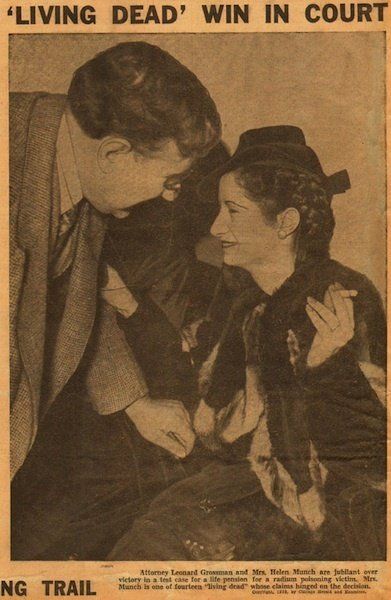

The news of their success swept around the nation and inspired women in Ottawa, Illinois to file complaints with the Illinois Industrial Commission against the Radium Dial Company there. But they were continuously denied compensation until the late 1930s when yet another group of brave women hired lawyer Leonard Grossman to fight on their behalf.

Unfortunately for these girls, the Radium Dial Company had closed by then and was only demanded to pay $2,000 each for their indiscretions. Still, even they fought tooth and nail against the suit, appealing to the Supreme Court EIGHT TIMES, until they were finally made to pay in 1939. And after years of medical bills and legal fees, the women's final rewards were not as substantial or as helpful.